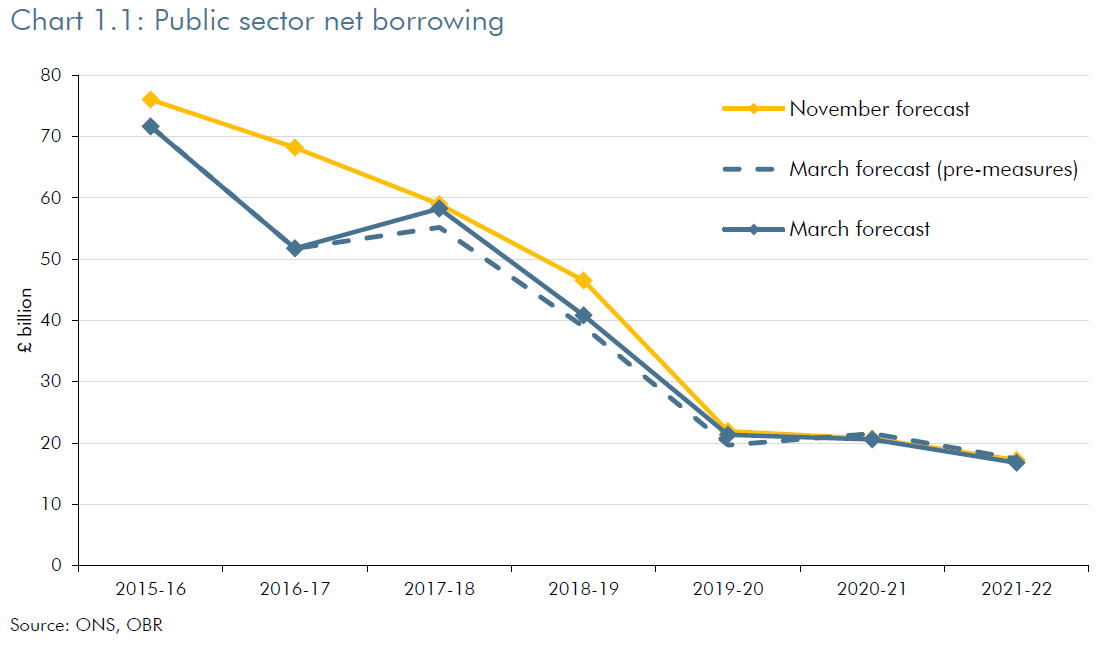

Public sector net borrowing is likely to be significantly lower this year than we anticipated at the time of the Autumn Statement in November, largely reflecting one-off factors and timing effects that flatter the figures at the expense of next year. So much so, in fact, that borrowing is now forecast to rise in 2017-18 before returning to a very similar downward trajectory to that we anticipated in November. This leaves the Chancellor on course to meet his target for structural borrowing in 2020-21 with room to spare, but not yet to achieve his goal of balancing the public finances “at the earliest possible date in the next Parliament”.

The deficit is now forecast to come in at £51.7 billion this year, down from the £68.2 billion we forecast in November (Chart 1.1). We now expect the deficit to increase by £6.5 billion next year rather than shrinking by £7.2 billion (adjusted for a change in how the ONS records corporate taxes). Factors explaining this turnaround include changes in the timing of contribution requests from the European Union, evidence of greater income shifting to beat the April 2016 rise in dividend taxation, and changes in the timing of corporation tax payments. Budget policy decisions will also push up public spending next year, whereas government departments appear to be underspending this year by more than expected.

The Budget decisions that the Treasury has chosen to report on its ‘scorecard’ imply a modest short-term giveaway of around £1.7 billion in 2017-18, dominated by additional funding for local authorities to deliver adult social care. This is followed by a modest medium-term takeaway averaging around £750 million a year from 2019-20 onwards. This includes an increase in National Insurance contributions on self-employment profits and reducing the generosity of the new dividend tax allowance.

Taking policy changes excluded from the scorecard and indirect effects into account, the total impact of the Budget policy decisions is a giveaway of £3.1 billion in 2017-18. The modest takeaway begins in 2020-21. The biggest non-scorecard policy effects arise from the Ministry of Justice’s decision to reduce the personal injury discount rate, which will substantially increase the size of one-off settlement payments. The Government has set aside an extra £1.2 billion a year to meet the expected costs to the public sector (notably to the NHS Litigation Authority). The change is also expected to increase insurance premiums, boosting receipts from insurance premium tax. But as that feeds through to inflation – particularly RPI inflation – it will increase debt interest via accrued interest on index-linked gilts. There is a small offset from higher excise duties, which are revalorised using the RPI.

Developments in the economy since November have had a relatively modest impact on the public finances. The first estimate of real GDP growth for 2016 as a whole was slightly weaker than we anticipated in November, but with momentum strengthening through the year rather than slowing as earlier vintages of data and our November forecast suggested. With business investment falling as predicted, this largely reflected stronger-than-expected growth in consumer spending, which significantly outpaced growth in incomes. This will have contributed to recent strength in tax revenues, but consumer spending growth cannot continue to outpace income growth by such a margin indefinitely.

Looking ahead, we expect real GDP growth to moderate during the first half of 2017, as rising inflation squeezes household budgets and real consumer spending. The relatively strong start to the year implies 2.0 per cent growth in real GDP in 2017 as a whole, up from 1.4 per cent in November, with small downward revisions thereafter reflecting the consequently smaller margin of spare capacity. Thanks largely to a weaker outlook for whole economy inflation, we expect weaker cumulative growth in nominal GDP over the forecast than in November, while its composition is also slightly less favourable for tax receipts. We have made no changes to our policy assumptions regarding Brexit.

Taking both forecast and Budget policy changes into account, we expect the deficit (in both headline and structural terms) to fall from 2.6 per cent of GDP this year to around 1 per cent in 2019-20 and then to edge slightly lower in the subsequent two years. We still expect debt to peak as a share of GDP in 2017-18 and to fall thereafter. So the Government remains on track to meet its targets for the structural deficit and public sector net debt.

But the Government does not appear to be on track to meet its stated fiscal objective to “return the public finances to balance at the earliest possible date in the next Parliament”. The deficit falls little in 2020-21 and 2021-22, while the ageing population and cost pressures in health are likely to put upward pressure on the deficit in the next Parliament.