The charts below show locally financed current and capital spending in cash terms and as a share of national income (GDP). Spending measured in cash terms is a simple metric for analysing trends over time. But without putting the cash amount into context – by asking how much national income is devoted to different types of public spending – interpreting changes in cash spending is difficult, particularly over long time periods.

Trends in spending as a share of GDP are useful to understand how spending moves in line with the underlying economic activity that ultimately finances it via taxation. In cash terms, both spending and GDP will tend to rise over time because of population growth and inflation. Spending as a share of GDP is the most relevant metric when considering the sustainability of the public finances.

Current locally financed expenditure as a share of GDP has been steadily increasing from 2012-13, when it represented 1.6 per cent of GDP, to 2018-19, where it reached a peak of 2.4 per cent of GDP. This reflects several factors including English local authorities drawing down on their reserves and higher income from council tax and business rates. In 2020-21 there was a significant decrease in locally financed expenditure, which fell to 1.9 per cent of GDP, largely a result of increased funding provided by central government to offset the effects of measures announced in response to Covid-19 (such as business rates relief) which reduced the income generated by local authorities for self-financing. In 2021-22, self-financed current spending as a per cent of GDP remained depressed at 1.9 per cent. It then returned to pre-pandemic levels in 2022-23, and is expected to remain at broadly these levels as a share of GDP over the remainder of the forecast.

Capital locally financed expenditure – mostly local spending on investment projects – as a share of GDP has been uneven across years, decreasing by nearly 40 per cent as a share of GDP from 2010-11 to 2012-13, remaining relatively constant for the next five years, and then increasing by 55 per cent in 2017-18 to a peak of 0.7 per cent of GDP. It then fell slightly, reaching 0.5 per cent of GDP in 2021-22. The nature of capital projects contributes to this uneven profile, with history suggesting that the level and timing of expenditure is subject to considerable uncertainty.

Capital expenditure continues to decline gradually as a share of GDP over our forecast, to 0.3 per cent of GDP in 2027-28. This fall in capital expenditure, particularly at the start of the forecast, reflects several factors. First, we expect capital spending by Transport for London subsidiaries to decline as construction of Crossrail is expected to have been completed by the end of the forecast. Second, reflecting recent outturn data, information from sector experts and changes in local authority behaviour, we expect capital spending financed by prudential borrowing to taper off. And third, recent supply chain shortages (from a combination of Brexit, Covid and the war in Ukraine) have led to expected delays in many capital projects.

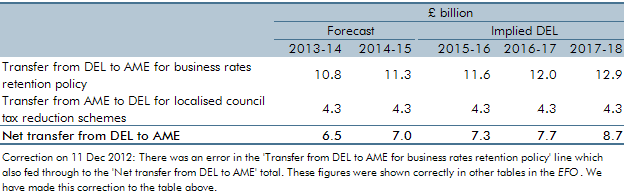

Note: Current locally financed expenditure outturn data have been adjusted for the effect of localising English and Welsh business rates (a DEL to AME switch), so as to ensure they are consistent and comparable over time.

More detail on our March 2023 forecast and how it was revised relative to our previous forecast in November 2022 was provided in paragraph 4.61 of our March 2023 EFO.

Back to top