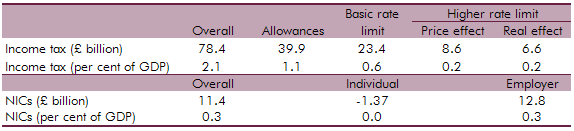

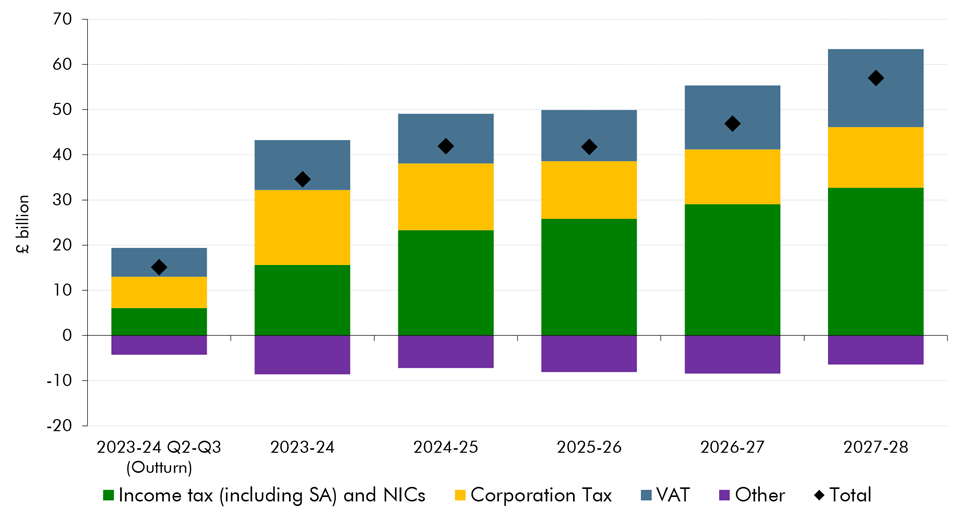

Taxes on different forms of personal income provide the biggest source of revenue for government. In 2024-25 we estimate that income tax will raise £302.7 billion. This represents 26.6 per cent of all receipts and is equivalent to around £10,400 per household and 10.9 per cent of national income.

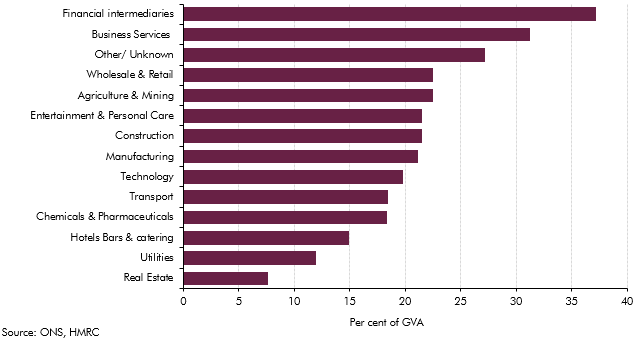

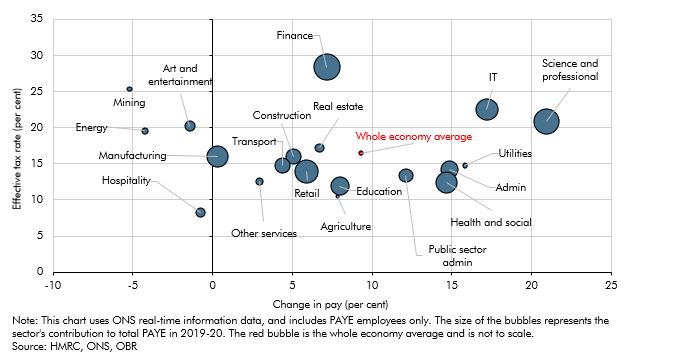

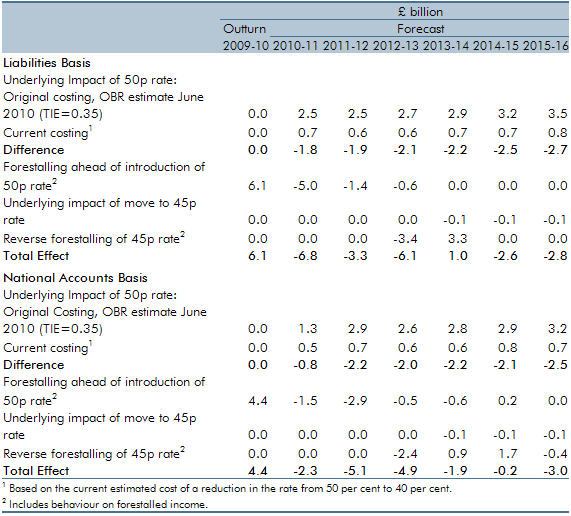

The main reason that income tax is the biggest source of revenue is that personal income makes up the majority of total national income. There are many sources of personal income on which income tax is levied. These include: labour income (the wages and salaries of employees and earnings of the self-employed), income from investments (including interest on savings and the rental income from buy-to-let properties), income from dividends and pensions income (from both the state pension and any occupational or private pensions).

Income tax is collected in a variety of different ways:

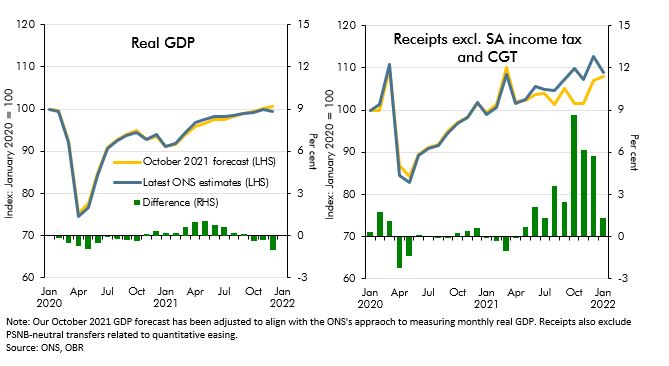

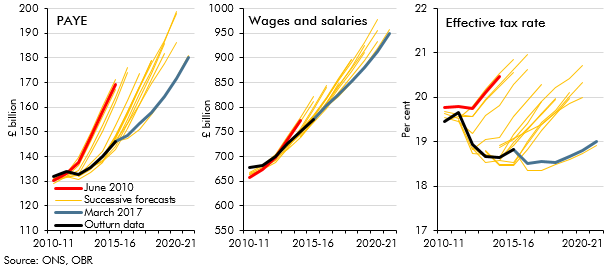

- For the majority of employees, it is paid via the pay-as-you-earn (PAYE) system. The amount of tax to be paid is calculated by the employer and transferred directly to the tax authorities (HMRC). This is also known as being deducted at source. It means the individual does not need to deal directly with HMRC and that the tax is paid promptly.

- For some taxpayers, such as the self-employed, it is paid via the self-assessment (SA) system. The amount of tax to be paid is calculated by the individual and declared on a tax return sent to HMRC. Tax returns and associated payments are completed after the tax year has ended – in most cases in the following January (so January 2024 for the 2022-23 tax year).

- Other smaller sources of income tax include company income tax, non-SA repayments (for example, when employees have paid too much tax through the PAYE system), investigation settlements, Accounting for Tax (AfT), and some receipts that cannot be allocated to a particular source.

Some income tax has already been devolved to the Scottish Parliament and the National Assembly for Wales. For more information see our webpages on fiscal devolution.

For most employees, National Insurance contributions (NICs) are also deducted at source, while the self-employed pay NICs via SA.